LITTLE PIM BLOG

How Does Learning a Language Change Your Child's Brain?

It is truly never too early to start teaching your child a second language--in fact, the earlier she's introduced to another language, the easier it is to master. The way a child's brain develops makes language learning one of the earliest skills they can master--before they can crawl, hold a toy, or speak, they can hear--and their brains can process and retain the sounds and words they're exposed to.

It is truly never too early to start teaching your child a second language--in fact, the earlier she's introduced to another language, the easier it is to master. The way a child's brain develops makes language learning one of the earliest skills they can master--before they can crawl, hold a toy, or speak, they can hear--and their brains can process and retain the sounds and words they're exposed to.

Pediatric Brain Development

The human brain is the only organ that is 80% developed by the age of two--and all the neurons your child will ever have are already present by then--about 100 billion. The synapses that connect the neurons have not developed; there are about 2500 per neuron at birth, and 15,000 by the time a child is three. As your child grows, the connectors continue to expand and the neurons and neurotransmitters do their magic until the brain is fully mature--in the early twenties.

Children have "windows of opportunity" in brain development; sensitive times when specific kinds of learning happen. There's a reason to expect your child's first words at 8 or 9 months, and their first steps around a year--these are the times the circuits wiring the brain for speech and balance go into overdrive. Babies have fuzzy vision when they are born; it's not until they're between 8 and 16 weeks that the synapses that control sight start to connect, and your baby responds to visual cues for the first time.

Neurologists believe that we are most receptive to learning a language during the first ten years. The brain starts to build the neural network it needs when a child hears the same sounds repeated, and as she learns words and sounds, the neural network explodes. She picks up on household conversations, music, stories, and any sounds she hears, and thus learns her native language.

The Right Time To Introduce A Second Language

There is no "right time" to start teaching a second language--experts in pediatric neurology only agree that by the late teens, a child's ability to become truly fluent in other languages decreases. If you live in a bilingual household, you've noticed how effortlessly your children have picked up both languages--so it's never too early to begin teaching a second--or third--language.

The above-mentioned windows of opportunity for learning certainly apply to languages. If you haven't started another language by his first birthday, wait until he's about two and a half--when he's gotten a solid grasp of his native language, and has a large vocabulary. Beyond toddlerhood, any time is fine to start teaching a second language.

What Are The Benefits Of A Second Language?

Some parents wonder why they should teach their children to be bilingual? Are there any real benefits? The answer is a most emphatic Yes. Children who know multiple languages exhibit the following characteristics.

Improved mental acuity

More imaginative and creative thinkers, better understanding of abstract concepts

Better understanding of the native language

Awareness of more than one point of view in a given situation, see a variety of perspectives

Improved ear for listening, and sensitivity to language

Improved social skills and ability to understand nuance

Neuroplasticity And Second Languages

Neuroplasticity has become a buzzword of late in brain research circles, and the consensus is that it is a real phenomenon, one that is advantageous for future neural flexibility.

Neuroplasticity is the brain's ability to create new connections and pathways and change the wiring of the circuits. There are two kinds of neuroplasticity, structural and functional. Structural neuroplasticity is a change in the overall strength of the neurons or synapses, regardless of whether the connections grow stronger or weaker--a change in the actual structure of the brain. Functional neuroplasticity refers to permanent changes in synapses due to development and learning.

Neuroplasticity in children is more defined, with four distinct types.

Adaptive--brain changes that occur when a special skill is learned and the brain adapts to that skill

Impaired--changes due to acquired disorders or genetics

Excessive--rewiring of the brain that results in new, maladaptive pathways that can cause disorders or disabilities

Plasticity For Injury--pathway develop that make injury more likely

These four traits are more pronounced in young children, allowing them to recover more quickly from injury or illness. For educational purposes, the adaptive neuroplasticity is relevant; learning a new language expands the pathways and neurons in the brain. One fascinating thing about neurons is that of the 100 billion a child is born with, the "use it or lose it" philosophy applies--any of the trillions of neurons in the brain that aren't connected eventually die off. Learning new things that force new synapse connections keeps those neurons active in the brain's circuitry--structural neuroplasticity.

Cultural Awareness

Learning a second or third language doesn't happen in a vacuum, especially with children. So much of their instruction is interactive, they learn about native cultures and traditions while they are learning the language itself. Knowledge of other cultures helps children understand more social nuance and non-verbal cues, highly desirable traits in a digital world where so much communication is digital.

Being bilingual also contributes to what the French psychologist Jean Piaget called "decentering"--becoming less self-centered and ego-driven, and more empathetic to others. This is the manifestation of the ability to see a range of perspectives for a given situation, which is a lot of adult-speak for saying that bilingual children tend to be more mature than their monolingual peers.

Executive Function And Cognitive Ability

Bilingual children also have better executive function--they have highly developed communication skills that allow them to reason their way through complex problems and ideas, and then expressing their thoughts in a clear manner. Strong executive function will come in handy throughout their academic and professional careers. Cognitive flexibility is also more pronounced when children know a second language--they can better filter through unnecessary information and target the task at hand.

Looking ahead, bilingualism and neuroplasticity are thought to be two ways to deter memory loss and even Alzheimer's disease in adults.

Learning a second or third language does nothing but benefit children, and it's never too early to get started. At Little Pim, we use a natural immersion teaching method for our young pupils, contact us today to learn more about our language programs.

Sources:

https://extension.umaine.edu/publications/4356e/

https://positivepsychologyprogram.com/neuroplasticity/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2989000/

https://www.muzzybbc.com/bilingual-benefits-for-kids

Photo by Colin Maynard on Unsplash

Benefits of Raising Bilingual Children on Fox 5

Recently on Fox 5 NY, the International Academy of New York discussed the benefits of raising bilingual children, sharing that their students spend around 40% of their week functioning in either Mandarin or Spanish. Research shows that some of the benefits of raising bilingual children include:

- Children are much more focused and less distracted

- They are more able to switch tasks spontaneously

- They have more flexible and nimble brains

- By middle school, bilingual kids typically outperform their peers in both math and verbal standardized tests

The interview also explains that human contact is important when teaching children a new language. Singing, reading, and talking with your children in the new language and taking children to cultural events also help encourage language learning. At Little Pim, we believe introducing your child to a new language at an early age can give your child many advantages. The best time to learn a language is under the age of 6. Don't miss the window of opportunity when it's easy for them to learn. Invest in their future…A little language goes a long way.

The Edge of Extinction

What do snow leopards, African wild dogs, black rhinos, and the Arikara language of the North Dakotan indigenous people have in common? They are all endangered. Just as species’ extinctions threaten the food chain and thereby the ecosystem, language extinctions hurt cultural diversity and thereby our society. To best understand the harsh reality of language extinction, we should investigate some statistics. While differentiating between unique languages and dialects, or just variations of the same language, is very difficult, researchers agree there are between 5,000-7,000+ languages alive today. Studies project that up to 50% of these languages will die out by the end of the century. Some even say the figure is higher at 80%, That is one language dying every few months! This slow and steady leak of linguistic and cultural diversity must be plugged for the sake of our children gaining the exposure to different thoughts and ways of life- exposure that stimulates appreciation and innovation. Admittedly, we, here at Little Pim, do not teach endangered languages, nor have we discussed them in prior blogs. We do, however, always hope to impart that a language is:

- Powerful in the classroom, in the workplace, and on the street

- Empowering in its ability to help cultivate creativity, cultural awareness, problem-solving skills, and pride in one’s roots

- Effectively important to personal and societal growth

In spreading this message in the past (as we will continue to do in the future), we hopefully indirectly made the case for the preservation of dying languages. Additionally, in teaching what are currently actively used languages, we aim to prevent their downfall into the endangered category one day. Yet, today, in this article, we will take a firmer stand for endangered languages, giving them a voice that might otherwise soon be taken away. It is with this voice that endangered languages might return from the edge of extinction.

It is with power in numbers that we can spread the word and reach someone in a position to change an endangered language’s course, so share this if you like the rest of the article. I will explain how we classify levels of endangerment, expound on why you and your family should care, and share what YOU can do to create a better future in which we maintain cultural diversity and awareness.

How do we know when a language is dead?

There are two main measurements of a language’s vitality, the number of speakers and the number of avenues of use.

Number of Speakers

Many languages can be said to have few speakers, but the word “few” is loose and open to interpretation. Determining the exact number of speakers of a language, however, allows linguists to be specific in distinguishing between levels of endangerment. Arikara, which you may recall is in our backyard in North Dakota, is a critically endangered language, with only 3 speakers still alive while the Cherokee language spoken in Oklahoma is classified as a vulnerable language, with only 1,000 speakers.

Number of Functions

The number of functions a language takes on, whether that be in prayer, in scripture, in school, in ceremonies, etc. can quantitatively represent a language’s vitality, because the more sectors of life the language is involved in, the more spoken it must be, and the more it veers away from the edge of extinction.

Some other factors linguists consider with regards to a language’s vitality are the age range of speakers, the number of speakers adopting a second language, the population size of the ethnic group the language is connected to, and the rate of migration into and out of the epicenter of the language.

Why do we care?

In history, conquered civilizations have had to adopt the language of their conqueror in order to fit into their social structure and economy. This is the case because language is so integral to a culture. From writing literature, carrying out rituals and practicing religion to voting in elections, all the human interactions associated with a culture involve written or spoken word. Effectively when a language dies, the culture associated with it dwindles away as well. If 50%-90% of languages die within the century, 50%-90% of existing cultures will likely die as well.

Many of these cultures that will die out only possess oral histories, so we will lose out on the knowledge they have gained from years and years of experience. Even if some of the cultures whose languages die have been documented, without active speakers, their thoughts and practices will likely be left behind in favor of the ones possessed by the dominant cultures and languages. Accordingly, our future society will lack in a diversity of thought and practice due to a lack of cultural diversity. Not only do we lose diversity of culture and thereby thought when languages die, but also when people conform to speaking one language, as is the case with English in the business world. If we continue along this path, we will become a monolingual, culturally homogenous society. In such a society, people might communicate efficiently because they speak the same language, but creativity would be strangled and progress slowed.

What can we do about it?

To prevent the fate of becoming a uniform society, we must recognize that cultural exchange is a two-way street. People speaking endangered languages are learning other languages to be able to interact with members of their extended community. While it may be hard for us to learn endangered languages, we can educate ourselves on which ones are endangered and why, learn about the cultures the endangered languages are from, and encourage their preservation. For example, the Arikara people were originally a semi-nomadic community that expertly harvested corn and tobacco. This mastery of the land gave way to power over other groups living in the plains until smallpox hit. Would this knowledge of the land past on from generation to generation in their language be lost in translation if the language died? Time will unfortunately tell.

Moreover, to avoid one major language from pushing out the others in the future, English-speaking people could learn other languages to communicate with non-English-speaking people, tapping into a whole wealth of knowledge they otherwise wouldn’t have access to. We cannot become complacent just because English is the “language of business.” Little Pim can open your child’s eyes to these other languages and vibrant cultures in the click of a button… literally. Check out our new iOS app!

Live in a Spanish-speaking community? Try our Spanish for Kids program.

Want to know more than the words for French foods on the bistro menu? Try our French for Kids program.

Works Cited:

https://www.linguisticsociety.org/content/what-endangered-language

https://www.ethnologue.com/endangered-languages

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_endangered_languages_in_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arikara

Featured Photo by Mark Rasmuson on Unsplash

10 Words English Speakers Are Missing Out On

Uh um eh. We often find ourselves tripping on our words. This inability to articulate our thoughts can be the unfortunate side effect of nerves when addressing a crowd, discomfort talking to a stranger, or tiredness after a late night. However, it’s not always our fault at all. In fact, the English language is missing some words to succinctly describe a situation or feeling. Below is a list of just 10 of these words in foreign languages that efficiently express sentence-long concepts in English. Fun fact: the concepts that the English language doesn’t have words to describe are often unpopular, unaccepted or previously non-existent in our culture, which reveals how critical a role culture plays in language evolution. You may not want to integrate these words into your daily English conversation, but they are perfect for trivia or an icebreaker and they shed light on the power of language to provide speakers with the agency to voice thoughts.

1. German: kummerspeck

Ever drown your sorrows in chocolates after a heartbreak or dive into a pint of ice cream after a cruel day at the office? If you have fallen victim to the emotion-induced indulgence and seen progress in your cookie pack instead of six-pack, you can probably relate to this word, which directly translates to mean “grief bacon.”

2. Japanese: wabi sabi

In English, we sometimes call things “perfectly imperfect.” The Japanese have eloquently expounded on this oxymoron by giving a name to the ability to find the beauty in flaws and to accept life’s cyclic nature of growth and decay. American singer Lana Del Ray’s “Young and Beautiful” asks “Will you still love me when I’m no longer young and beautiful?” and is therefore somewhat of an ode to this this subject matter.

3. French: seigneur-terraces

In Starbucks, you can always spot the people who haven’t bought a lot but are really just there to hang out, read a book, research for a paper, answer emails, or just kinda people watch. You know who you are. Well, the French have ingeniously come up with a word to describe these individuals who should owe rent to the coffee shop.

4. Italian: slampadato

The girl or guy at the party who is just a little bit too orange for comfort and definitely owns a membership to the tanning salon is perfectly described by this one word.

5. Mexican Spanish: pena ajena

Overhearing the silence after a colleague makes a bad joke to a group of coworkers or watching on as a woman in heels trips down the steps to the subway can cause you to cringe yourself. This discomfort born of others’ actions and the natural human urge to sympathize is described by this Spanish expression. While there was never a way to describe this feeling in English, kids today have come up with the phrase “second-hand embarrassment.” This goes to show how our language is evolving to fill holes that other languages filled long ago.

6. Russian: toska

Friend: “Are you okay?”

You: “Not really.”

Friend: “What’s wrong?”

You: “I don’t know.”

Such a conversation might ensue when you feel an emptiness or lack of fulfillment that can’t be attached to anything specifically. You might desire something without knowing what that something is. We have all experienced it, but most of us bottle it up or sweep it under the rug, because it’s hard to communicate to those we trust and/or love. The Russians have crated a solution to this problem by having a word to describe this feeling.

7. Arabic: ya’aburnee

If you were assigned the task to write a paper analyzing Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, this Arabic word, meaning the desire to die before someone else, because life without him or her would be too difficult, could prove useful.

8. Portuguese: saudade

When your child loses his or her favorite stuffed animal to the devastating toilet plunge, he or she is suffering from this feeling: a yearning for something or someone that has been lost.

9. Chinese: yuan bei

The deal you have been staffed to at your job, the deal whose pitch you spent sleepless nights writing, you ran by seventeen different superiors, you revised thousands of times, and you cried about more than you would like to admit, just closed. That inexplicable sense of pride in yourself and the perfection of your work is no longer inexplicable thanks to this Chinese word.

10. Korean: dapjeongneo

When you ask your significant other, “Does this piece of clothing make me look fat?” or “Do you even think I’m pretty/handsome?” There is only one acceptable answer. If you have ever been on the receiving end of those questions, you know that. This concept of there being a “correct” answer that a person has no choice but to give has its own recently added word in Korean but no English counterpart as of yet.

Works Cited:

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/10/more-languages-better-brain/381193/

http://mentalfloss.com/article/50698/38-wonderful-foreign-words-we-could-use-english

http://www.popsci.com/science/article/2013-01/emotions-which-there-are-no-english-words-infographic

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20170126-the-untranslatable-emotions-you-never-knew-you-had

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.lingholic.com/15-untranslatable-words-wish-existed-english/amp/

Did You Know Every Parent is Bilingual?

“Don’t talk to me like a baby!” You might be familiar with this phrase if you have an older child or have gotten into a spat with a partner or colleague. While baby talk can be construed as condescending when directed at an older individual, it is actually critical to the cognitive development and language learning of infants and toddlers. Linguists and child psychologists refer to baby talk more often as child-directed speech. Many aspects of child-directed speech allow it to facilitate language learning, such as the following:

High-pitch and tone variation

These qualities characteristic of child-directed speech make it more stimulating, effectively causing the words spoken to be more memorable.

Repetition

Children’s first words are often the ones they hear the most often. This is because repetition is a key component that drives memorization. Thus, the repetition common in child-directed speech helps children learn the language.

Reduplication

When using child-directed speech, parents often say expressions like “woof woof” and “beep beep.” This specific type of repetition, called reduplication, also helps with memorization and language learning.

Isolation

Sentences and phrases formed when using child-directed speech tend to include the most important word at the end. For example, parents might say “oh look at the cute little doggy” instead of “there is a cute dog right over there.” This isolation of the word dog helps children learn the word, because they can separate the noises associated with saying the word from the rest of the phrase.

When children imitate child-directed speech, they are actually imitating and learning proper grammar.

One theory about language acquisition is that much of children’s knowledge is innate. Specifically, some linguists have asserted that children are born with knowledge of syntactic structures and then utilize imitation to learn words to fit into those structures. Complete foreknowledge of grammatical structure prior to birth seems unlikely, especially given this structure is unique to every language. In fact, a closer look at child-directed speech reveals that it is far more properly structured than casual, fragmented conversation between adults. When children imitate child-directed speech, they are actually imitating and learning proper grammar. While children’s capacity to learn may be innate, their language learning is in many ways an imitation game.

Each and every parent around the world is fluent in both his or her native tongue and child-directed speech.

Child-directed speech doesn’t just exist here in the United States and with English, but in a plethora of cultures and with a multitude of languages. Each and every parent around the world is fluent in both his or her native tongue and child-directed speech. This form of bilingualism is pertinent to infants’ and toddlers’ first language acquisition and cognitive development.

Just like child-directed speech improves cognitive development in infants and toddlers, so does learning a foreign language.

While parents adopt this child-directed speech with ease, infants and toddlers could also adopt another language with ease. Children can learn more than one language at a time without conflating the two or hindering their progress towards fluency in their native language. In fact, children are noted to become more native-like speakers in a foreign language if they learn the language at a very young age. Just like child-directed speech improves cognitive development in infants and toddlers, so does learning a foreign language. As it happens, children who learn another language at a young age are said to be able to concentrate better in spite of outside stimulus, an important skill in an age when technology, among other things, has become a huge distraction.

While all parents are fluent in their native tongue and child-directed speech, not all parents are fluent in other foreign languages… cue Little Pim.

In conclusion, while many people may not appreciate when you speak to them like a baby, your infant or toddler loves it. Your child’s engagement with child-directed speech makes it a useful tool to teach words and proper grammatical structures. Via aiding in first language acquisition, child-directed speech improves a child’s cognitive development, just as learning a foreign language can. While all parents are fluent in their native tongue and child-directed speech, not all parents are fluent in other foreign languages… cue Little Pim. Let us join you and your child on a path towards intellectual growth.

Works Cited:

http://pandora.cii.wwu.edu/vajda/ling201/test4materials/ChildLangAcquisition.htm

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2011-05-motherese-important-children-language.html

http://news.cornell.edu/stories/2009/05/learning-second-language-good-childhood-mind-medicine

The Advantage of Multilingualism

The traditional view of imposing language learning on children is that the two languages would interfere with each other and slow literacy learning. There is some evidence that learning two languages in early education does impose additional stressors on the brain.

New evidence suggests that this stress actually improves mental ability.

The demand forces the brain to solve some fundamental learning problems which monolingual children never have to face.

The key difference between monolingual and bilingual children goes beyond the ability to control the suppression of one language and select the other language at will.

It seems to be about improvements in ability to monitor surroundings and sensitivity to the environment.

New studies indicate that the multilingual exposure is manifest in improved social skills in children.

These particular cognitive abilities, are improved through multilingual education:

The ability to monitor the environment is especially important for social interaction.

Children who have learned how to select among learned languages are better at considering the point of view of others.

This is a critical developmental faculty that the pioneering developmental psychologist Jean Piaget called "decentering."

Children in multilingual environments have ample practice considering the point of view of others.

They are also more aware that there is more than one point of view.

Children who learn more than one language are often raised in environments surrounded by multiple languages and cultures.

They learn early how to see the world through widely varied eyes, a range of different perspectives.

They learn to account for other perspectives in their communication and their attitude development.

Not only do they become more decentered (in Piaget's terms) but they become less "egocentric" as well.

At Little Pim, we believe that all children deserve to learn a second language. We use a natural immersive method of teaching. Please contact us to learn more.

The Benefits of Starting Early: Why Your Kids Need to Learn Another Language Now

Our world is no longer constrained by the borders on a map. It has become increasingly global in every realm from business to social relationships. For a child to flourish in this new and diverse climate, it's important that they get multilingual exposure and begin learning a foreign language before age 6 to experience the most benefits. In most non-English-speaking nations, particularly in Europe; instruction in another language is mandatory. Not only are children taught a second language, but they are often are raised in an environment where they are exposed to multiple languages; necessitating the acquisition of multiple tongues.

In places such as Switzerland and Belgium, there are many recognized languages and dialects, and therefore it is not uncommon for someone to speak three or four different languages. Meanwhile, the vast majority of English-speaking countries have no national mandate for teaching children a second language.

In the United States, foreign language instruction is lacking. According to an article in The Atlantic, only 1% of American adults were proficient in a foreign language. Many aren't exposed to a foreign language until their college years.

The United States isn't the only nation that fails to expose students to foreign languages at a critical age. According to Arlene Harris in her article, Learning the Lingo: Taking up a Foreign Language Before We're 3?; Ireland "lags behind the rest of Europe and should be starting kids off before they're 3."

It is a predominately western problem, perhaps because we are leaving an era dominated by English-speaking business and culture. With the advent of the Internet, success has spread in every direction; including eastward, with the future of industry looking strongly toward Asia and the Pacific. Children must learn languages early to stay ahead of the competition.

Most countries in Europe begin language instruction around the age of seven or earlier. It's not only possible, but beneficial for the budding mind. According to Dr. David Carey, "“All The children can learn another language at an early age [...] [The] young brain, before the age of 5, is able to learn to speak another language without developing an accent — to speak it like a native."

Starting language learning early has documented benefits. The childhood brain is elastic and able to learn and retain a multitude of information that someone in their early 20's would struggle with. It's been documented that it's easier for children to learn a second language than adults, so why wait until college to begin learning such an important skill? Exposing your children early is critical, and Little Pim has the resources you need to get them going!

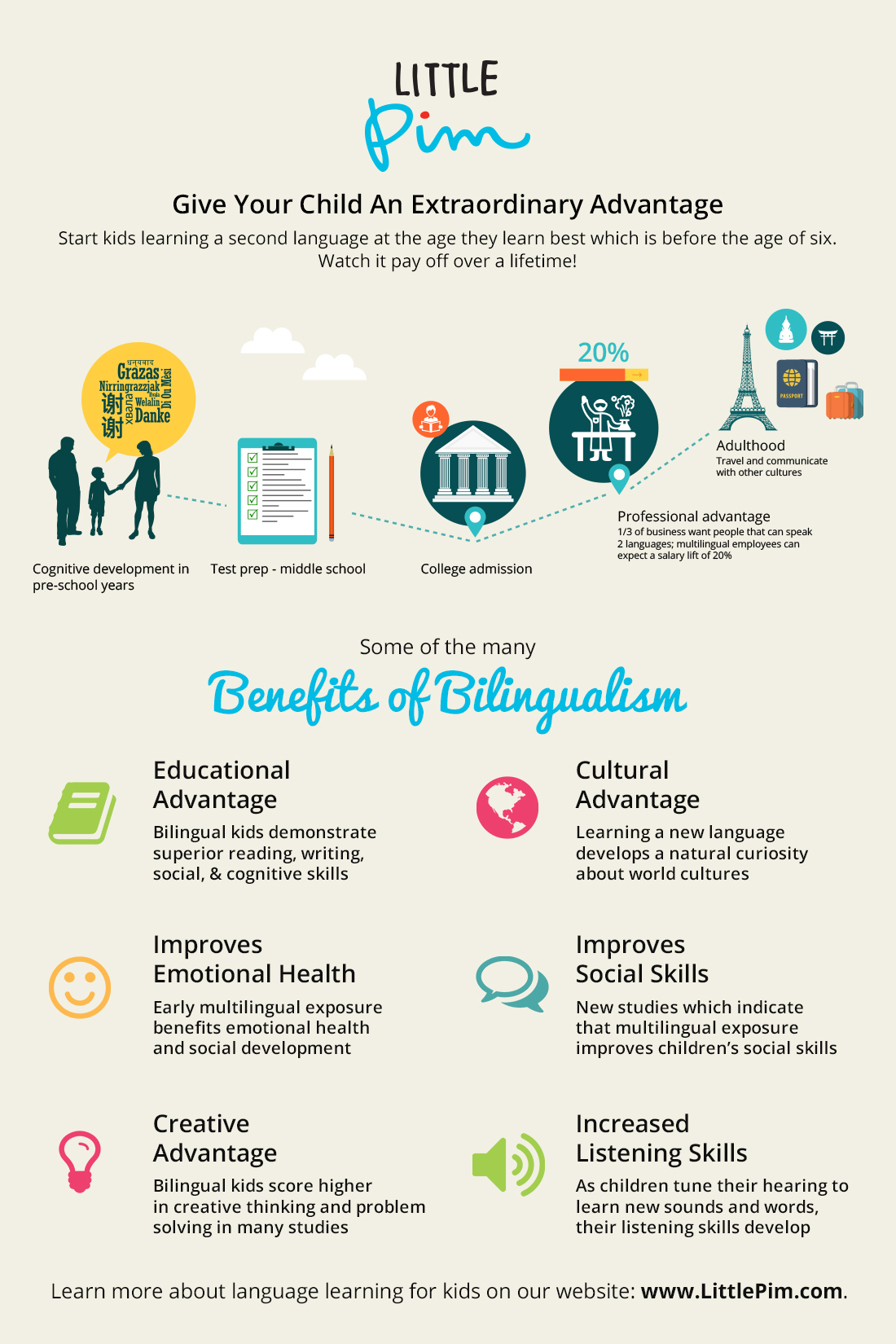

Infographic: The Benefits of Early Language Learning

Below is an infographic on some of the many benefits of teaching kids a second language at the age they learn best which is before the age of six. Give a child the gift of a second language and watch it pay off over a lifetime! Share this infographic with parents and teachers and explore more of the benefits of bilingualism on our website.

Brain Research: The Benefits of Bilingualism

Growing up knowing more than one language offers many benefits. Just knowing the language is the most obvious one, but the benefits extend to the way we think. An article on the NPR website by Anya Kamenetz, "6 Potential Brain Benefits of Bilingual Education," discusses these advantages. The article focuses on non-English speakers learning English, but English speakers who pick up a foreign language benefit too. The younger they start, the better, but children of all ages stand to sharpen their minds.

Keeping two languages separate in their heads exercises brain skills. The bilingual student has to know when to use one language, and when to use the other. Developing this skill helps in task switching, and spotting the social cues promotes empathy.

Another big benefit is "metalinguistic awareness" — the understanding of how language works. Learning more than one language means learning there's more than one way to say things. They learn about different ways to put words and ideas together. German doesn't have a word for "mind," but that's only because it doesn't draw the sharp distinction among "spirit," "mind," and "sense" that English does. That didn't stop Jung and Freud from going deep into the study of psychology.

A study at American University found that dual-language students outperformed English-only ones on reading. They could pull as much meaning out of sentences as students with better English skills but no foreign-language skills. They generally knew fewer English words, but their awareness of language made up for it.

The benefits may extend into old age. Kamenetz cites a Canadian study which finds that bilingual people with Alzheimer's disease don't suffer from cognitive impairment as early as monolingual ones. This could be because bilingualism gives a "cognitive reserve" that makes up for loss of brain function.

Learning a second language is a great way to expand a child's understanding of the world. Visit our website to learn how children can learn languages through Little Pim.

Bilingual Baby: When is the Best Time to Start?

The benefits of introducing your baby to another language are well documented. In our rapidly globalizing society, knowing a second (or third) language provides an obvious edge over the competition in the job market.

But, what about its impact on childhood development? While some would suggest that over-exposure to foreign language may cause delay in speaking, this assumption is both unproven and outweighed by the benefits dual-language babies experience as they grow.

We know the many benefits, so the question soon becomes: “When do we start?”

The answer is surprising. According to an article by the Intercultural Development Research Association, it may be most beneficial to begin second language exposure before six months of age. In a study by psychologist Janet Werker, infants as young as four months of age successfully discriminated syllables spoken by adults in two different languages. Dr. Werker’s work also determined a possible decline in foreign language acquisition after 10 months of age. To give your child their best start, you must begin early.

How is this so? The answer can be found in the complex world of the human brain. Our brains react uniquely to language learning at any age, even growing when stimulated by another language. While mankind can acquire a language at mostly any stage, it is exceptionally difficult to do so outside of childhood. From infancy to age five, the brain is capable of rapid language acquisition. Even so, there are varying degrees of acquisition, even for children. After six months of age, infants begin distinguishing the differing sounds of their native tongue and others. Beyond six months, exposing your little one to a brand new language will pose a challenge.

That is not to say that teaching your two year-old French is a bad idea! It is merely to say that the earlier you begin teaching your child, the better.

Though most babies wont utter their first words before eleven months of age, they develop complex mental vocabularies through the piecing together of “sound maps.” As they gather from what they are exposed to, an infant who hasn’t been immersed in another language during this delicate stage will not piece together adequate sound maps to differentiate another language.

The reason for this is rooted in the brain at birth. Children are born with 100 billion brain cells and the branching dendrites that connect them. The locations that these cells connect are called synapses; critical components in the development of the human brain. These synapses are thought to “fire” information from one cell to another in certain patterns that lead to information becoming “hardwired” in the brain. The synapses transmit information from the external senses to the brain via these patterns, thus causing the brain to interpret them, develop, and learn from them. From birth to age three, these complex synapses cause infants to develop 700 neural connections per second.

These synapses are critical in sound mapping, and at the age of six months, the infant brain has already begun to “lock in” these new patterns and has difficulty recognizing brand new ones. This is because although your baby is born with all of the neurons they’ll ever need, that doesn’t mean that they’ll “need” all 100 billion. Infancy to the age of three is filled not only with rapid neural expansion, but also with neural “pruning;” a process in which unnecessary connections are nixed and others are strengthened.

Exactly which connections are pruned and which are cultivated is partially influenced by a child’s environment. Synapses are cultivated or pruned in order of importance to ensure the easiest, most successful outcome possible for a functioning human being. If a function is not fostered during this stage, it is likely that the neural connections associated with it will fade. For the brain to see a skill as important, you must make it important.

To put it plainly, if you only speak to your child in English, the infant brain sees no reason to retain a neural pathway regarding the little Mandarin it has heard. Babies learn about their environment at every age and are internally motivated from birth to do so. Your baby wants to learn and does so by exploring and mimicking the world around them. They’re entirely capable of building a complex knowledge of Mandarin, Arabic, or Italian. So, why not feed their mind and start now?